The Warsaw Ghetto

|

| Janusz Korczak (1878-1942) |

On 1st September

1939 Germany invaded Poland. From mid-September Warsaw was besieged and by the

end of September the city had surrendered. In November 1940 the Nazis created

the Warsaw Ghetto, calling it the “Jüdischer Wohnbezirk” or “Jewish residential

district”.

It was the most

densely populated of all such ghettos created in Nazi-occupied Europe. Jews

from Warsaw and beyond were rounded up and forcibly herded into it. The

conditions were appalling, food and other essentials were very scarce and it

was vastly over-crowded.

Amongst those

forced into the Ghetto were Janusz Korczak and some 200 children and staff from

the orphanage he founded in Warsaw about 30 years earlier. Korczak was a

doctor, a successful author and teacher. When the Germans first invaded Warsaw

he refused to recognise their authority and ignored their regulations. This led

to him spending time in jail. Korczak received several offers from Polish

friends who were prepared to hide him on the "Aryan" side of the city

but he declined, as he would not abandon the children.

During the summer

of 1942 the Nazis began “deporting” residents from the Ghetto. They were

marched through the streets of Warsaw to the railway station, unaware of their

final destination. In fact they were being sent to the Treblinka extermination

camp. It gradually became clear to those still inside the ghetto that they were

to be sent to their deaths. Towards the end of 1942 there was a lull in these

deportations and it was during this time that resistance groups began to form.

The decision by the Nazis, in January 1943, to continue the deportations led to

the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising. In total more than 254,000 people were taken from

the Warsaw Ghetto to Treblinka, and murdered.

Janusz Korczak

was amongst those sent to Treblinka. On 5th August 1942 he, 12 members of his

staff and 192 children were rounded up by the Nazis and marched through the

streets of Warsaw to the railway station where they were forced onto the train

to Treblinka.

One eyewitness

remembered Korczak “marching, his head bent forward, holding the hand of a

child... the children were dressed in clean and meticulously cared for

clothes”. Another wrote, “He told the orphans they were going out to the

country, so they ought to be cheerful. At last they would be able to exchange

the horrible suffocating ghetto walls for meadows of flowers, streams where

they could bathe, woods full of berries and mushrooms. He told them to wear

their best clothes, and so they came out into the yard, two by two, nicely

dressed and in a happy mood.”

|

| Memorial to Janusz Korckak and the children at Treblinca |

|

|

|

As an

educationalist and an author of popular children’s books Korczak had an

international reputation. It has been claimed that the Nazis gave him an

opportunity to escape from the train to Treblinka but he refused, again because

he would not abandon the children.

This was the

tragic conclusion to a story that began some thirty years earlier when Janusz

Korczak visited a children’s home in Forest Hill, South-East London.

“Janusz Korczak”

was, in fact, the pen-name of Henryk Goldszmit. He was born in Warsaw in 1878

and adopted his pen-name, from a character in a Polish novel, when he began

writing in his early 20s.

Korczak described

his own schooling as “Strictness and boredom. Nothing was allowed. Alienation,

cold and suffocation.” When he was eleven Korczak’s world was shattered. For

some years his father suffered severe mental health problems and after several

breakdowns was sent to a mental institution, where he died. The family was

brought to the brink of poverty by this. Korczak managed to complete his

medical training and went into practice as a paediatrician. However, in 1910,

he decided to give up his medical practice and found an orphanage.

For him this was

a difficult decision to make. He realised that although medicine could care for

the body teaching could develop the mind. He wrote, "What a fever, a cough

or nausea is for the physician, so a smile, a tear or a blush should be for the

educator." He realised that in an orphanage he could combine both medicine

and teaching both “curing the sick child and nurturing the whole child”. The

orphanage would be “a just community whose young citizens would run their own

parliament, court of peers, and newspaper”. Korczak believed that children had

a right to be treated by adults with tenderness and respect, as equals. They

should be allowed, and helped, to grow into whoever they were meant to be. The

"unknown person inside is the hope for the future”.

In January 1911,

while he was making plans for the new orphanage, two close friends of his died. He was much saddened by their loss and seems to have suffered a period of

depression. This was not helped by his memory of his father’s death and his

fear that such depression was hereditary.

Visit to Forest

Hill

After the

cornerstone of the orphanage was laid on 14th June 1911 Korczak left for

England to visit orphanages but also, it has been suggested, to shake his

depression. It was during this time in London that he visited Forest Hill where

he was to have an experience that appears to have given him a clearer sense of

the direction his life should take.

|

| Horniman Gardens from the pond, looking towards the bandstand |

Korczak had

clearly been told about two children’s homes in Forest Hill and decided he

should see them. He wrote a detailed account of the visit, describing how he

took the tram from Victoria to Forest Hill. It seems he got off at Horniman

Gardens, at the tram stop by the museum. He describes, “a park – lawns, a large

lawn on a hill, the bandstand at the top seems small but on Sundays an

orchestra of forty musicians plays there. On the green hill children are

playing ball games. Lower down is a lake. Here they are launching boats and

model ships. Behind a hedge one can hear the rattle of a train and see the smoke

from the steam engine. A clock strikes the hour”. He also mentions a museum

that housed a mummy. Little has changed except that the small lake has been

drained, the railway line to the Crystal Palace closed in 1954 and the clock no

longer strikes.

Korczak then

walked towards the shopping centre where “the inhabitants can buy all they

need”. Continuing along Dartmouth Road he came to “a larger and grander

building – communal baths – a bath for two pennies, a swimming pool for one

penny – with separate pools for adults and children”. He speculates on how much

it cost to build and maintain the pools adding, “the parish paid towards it

all, and some lord topped it up”. In fact the parish donated the land and the

Earl of Dartmouth, who may well have donated some money, opened Forest Hill

Pools in 1885.

However, the

biggest surprise was the orphanage next to the pools, the Girls’ Industrial

Home, known as Louise House. The director greeted him politely and showed him

around "with no trace of German arrogance or French formality." He

saw the laundry, the sewing room and the embroidery workshop. He also visited

the Boys’ Home. Every child had a garden plot and kept rabbits, doves or guinea

pigs. He noted that the children all went to school for formal education. He

also mentioned the report books which still survive in the Lewisham Local

History & Archives Centre. On leaving Louise House Korczak signed the

visitors’ book “Janusz Korczak, Warsaw”. Unfortunately the visitors’ book does

not seem to have survived.

Korczak was aware

that a stranger from a distant country was not the sort of visitor that the

homes were used to. He commented on how he felt the staff saw him: “Warsaw? A

strange guest from far away. Why is he looking at everything with such

interest? What is so special about this place? The school? But there are

children, so of course there must be a school. The orphanage? But there are

orphans, so they must have somewhere to stay. A swimming pool? A playground?

But this is necessary. Yes, it is all necessary.”

In a letter

written to a friend in 1937 Korczak explained: "I remember the moment when

I decided not to make a home for myself. It was in a park near London. Instead

of having a son I chose the idea of serving the child and his rights”.

Korczak was

clearly deeply affected by his visit to the industrial homes. It seems that on

his way home he returned to Horniman Gardens to ponder over what he had seen.

He felt his own life had been "disordered, lonely, and cold," and

decided that as “the son of a madman” and as a Polish Jew in a country under

Russian occupation he had no right to bring a child into the world. He decided

that he would not take on the responsibility of marriage and a family but would

instead commit himself to “serving all children and their rights".

Korczak’s own

childhood had been difficult. When he was eleven his father became mentally ill

and died in a psychiatric hospital and at the time it was thought that such

illnesses might be inherited and this must have played on Korczak’s mind. At

the time he visited Louise House Korczak was thirty-three, almost the age his

father was when Korczak was born. He returned to Warsaw with a clear vision of

what he should do and how the orphanage should be run. In 1912 the orphanage

opened, with Korczak as director.

|

President Obama

during a ceremony in Janusz Korczak Square

at Yad Vashem Holocaust Museum in

Jerusalem.

Behind him is the

statue of Janusz Korczak

and the Children.

|

Korczak believed

that children had their own personalities and their own paths to follow. The

role of a parent or a teacher was not to impose other goals on a child, but to

help them achieve their own. Children had rights and their views should be

listened to. The children in his orphanage were encouraged to write their own

newspaper and they were involved in discussing and agreeing the rules.

"Out of a mad soul we forge a sane deed," he wrote in later years.

The deed was "a vow to uphold the child and defend his rights."

Korczak's ideas

influenced the development of free schools such as Dartington Hall and A S

Neil’s Summerhill in the 1920s and there was even a school in Sydenham

influenced by his ideas, the Kirkdale Free School at 186 Kirkdale. It opened in

1964 and closed in the 1980s. Korczak’s work on children’s rights was also used

as the basis for the UN Convention of the Rights of the Child which is used to

this day by governments around the world.

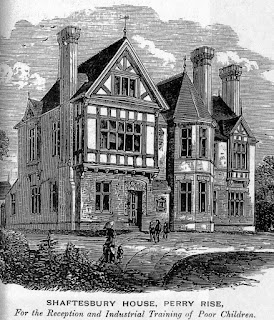

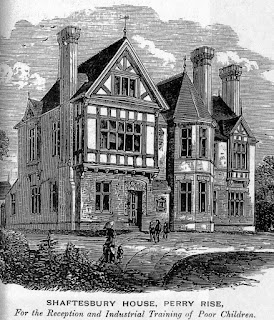

Louise House and

Shaftesbury House

The industrial

homes that so impressed Janusz Korczak during his visit to Forest Hill

developed from the Ragged School movement of the mid-19th century. Whereas the

Ragged Schools offered a basic, free education to destitute children and

sufficient training to enable them to earn an honest living, the children still

lived in what were often appalling domestic conditions.

However there

were some who believed that such children could only prosper if they could

leave “the destitution of parents or influence of surroundings, which were very

likely to lead them into a life of crime”. They should be “rescued from the

perils of the street, fed, clothed, housed, educated and taught a trade”. The

industrial homes, often established in pleasant locations, provided that

refuge; they were intended to provide a “home” for children who had no home.

A group of local

philanthropists felt that Forest Hill offered a suitable environment for such a

home. Funds were raised and a small house at 17 Rojack Road, between Stanstead

Road and Rockbourne Road, was acquired. The Boys’ Industrial Home opened on 3rd

May 1873 for “the reception and industrial training of destitute boys”. At that

time it could accommodate just six boys.

|

| Nos. 3 and 4 Rojack Road in about 1881 |

The home was

funded by donations from local people. These included F J Horniman who made an

annual donation of 18 guineas (almost £1500 today), sufficient to support one

child for a year. Under the terms of his will this was to continue after his

death. Forest Hill’s other important tea-merchants, the Tetley family, were

also generous donors together with several dozen other local people. Clearly,

founding the home was the initiative of wealthy and benevolent Forest Hill and

Sydenham people.

Each application

for entry to the home, usually from a sponsor or parent, was considered by the

Industrial Homes committee. They decided whether those who applied for

admission were likely to benefit from their time in the home. They would accept

only those children who were aged between 7 and 10 and whom they knew to be

“destitute or the children of poverty-stricken parents” and would not consider

anybody who had already become involved in serious crime. Where possible “a

small weekly sum [was] expected from the parents” according to their means.

During his visit to Louise House Janusz Korczak wondered why an affluent area

like Forest Hill needed an orphanage but, of course, very few of the children

were actually from Forest Hill.

By 1875 the house

next door, 16 Rojack Road, became part of the boys’ home. At this time the boys

were training to be shoemakers. Their wares were sold to help raise funds for

the home, which, in 1875, raised £63 (more than £5,000 today). The boys also

chopped and bundled firewood and this too was sold.

For their formal

education the children attended local schools, initially Christ Church National

School, Perry Vale (now called St George's Cof E) and Holy Trinity National School, Dartmouth Road but when

the non-denominational board schools opened the girls attended Sydenham Hill

School (now Kelvin Grove) and the boys went to Rathfern Road School.

By 1881 the need

for a home for girls was becoming apparent and so it was decided to make

arrangements for the reception of “a few of these little waifs, who are without

doubt on the verge of moral and spiritual ruin”. No. 16 Rojack Road was adapted

and on 20th July 1881 was opened as a Girls’ Home by the Earl of Shaftesbury.

In the same year a further two houses, 3 and 4 Rojack Road, became boys’ homes.

By this time there were 22 boys and 11 girls being cared for. By 1880 it was

already clear that these houses were inadequate and that there was a need for larger

and better-designed homes. A building fund was set up to achieve this.

In May 1884 a

purpose built boys’ industrial home, Shaftesbury House, Perry Rise, was opened

by the Lord Mayor of London in the presence of the Earl of Shaftesbury, who was

patron of the home.

In May 1884 a

purpose built boys’ industrial home, Shaftesbury House, Perry Rise, was opened

by the Lord Mayor of London in the presence of the Earl of Shaftesbury, who was

patron of the home.

The architect of

Shaftesbury House was Thomas Aldwinckle (1845-1920). Although he built

hospitals and workhouses across south-east England, including the old Lewisham

Baths, Brook Hospital and the water tower on Shooters Hill, and the important

Kentish Town baths, he was very much a local architect. He lived in Forest Hill

for almost all his working life and his house at 62 Dacres Road, which still

survives, was almost certainly designed by him.

The boys’ home

closed in about 1943 and the building needlessly demolished in 2000.

On 21st October

1889 Viscount Lewisham wrote to The Times announcing the decision to build a

new girls’ home and laundry and appealing for funds. On 17th June 1890 Princess

Louise laid the foundation stone of the new building on a site in Dartmouth

Road. This was the building visited by Janusz Korczak in 1911. It is one of

four significant buildings on this part of Dartmouth Road, three of them listed

Grade II. The other buildings are Holy Trinity School, Forest Hill Library and

Forest Hill Pools. They were built within 25 years of each other with a shared

common purpose, the health and welfare of less advantaged people in Forest

Hill, Sydenham and beyond. Between them they provided opportunities for

education, religious instruction, exercise, cleanliness and learning a trade.

Three of the four buildings are still in use for the purpose for which they

were originally intended.

The history of

the site on which these buildings were erected began in 1819 when Sydenham Common

(500 acres of open land in Upper Sydenham and Forest Hill) was enclosed. Since

time immemorial the common had provided local people with certain rights such

as free access, grazing livestock, gathering firewood, hunting and holding

fairs. After the enclosure the common was divided into small plots that were

fenced to keep out trespassers. These plots were awarded to those who already

owned land in Lewisham. Thus, as so often happens, the wealthy benefitted at

the expense of the poor.

One of the beneficiaries

of the enclosure was the Parish of Lewisham, which was awarded the large field

on which these four buildings were to be erected. The field, which became known

as Vicar’s Field, was originally let as allotments to those who had lost their

common rights. As circumstances changed, the vicar (from 1854, when the parish

of St Bartholomew was created, the freeholder was the Vicar of St Bartholomew’s

Church) was persuaded to make parts of this field available for purposes he

deemed to be socially worthwhile. During the early 1870s Vicar’s Field was one

of the sites proposed for a public recreation ground but the vicar decided such

a use was not a good enough reason to deprive the poor of their allotments so

an alternative site was found, now known as Mayow Park.

However, the

vicar did agree to make part of the field available for a church school and in

1874 Holy Trinity National Schools opened. This was followed by the pools in

1885, Louise House in 1891 and finally the library in 1901.

|

| Louise House, with the library on the left, at about the time of Korczak's visit |

|

The foundation

stone of Louise House was laid by Princess Louise, Marchioness of Lorne and

daughter of Queen Victoria, on 17th June 1890. She retained an interest in the

industrial home that bore her name for many years. Thomas Aldwinckle, who also

designed Shaftesbury House and Forest Hill Pools, was the architect of Louise

House.

The house

remained a girls’ home (the word “Industrial” was carefully removed from the

fascia across the front of the building in about 1930) until the mid-1930s. By

1939 it was occupied by Air Raid Precautions and after the war it became a

maternity and child welfare centre. Louise House was closed and boarded-up in

2005 but is now being used as artists’ studios and its future seems secure. As

a rare survivor of a purpose built industrial home that is still largely intact

and also because of its significant link with Janusz Korczak English Heritage

listed the building Grade II.

Dietrich

Bonhoeffer

By an

extraordinary coincidence another heroic person who died opposing the Nazis

also had links with Forest Hill. In 1933 Dietrich Bonhoeffer was elected pastor

of the German Evangelical Church in Dacres Road, Sydenham and moved into a flat

above the German school at 2 Manor Mount, Forest Hill. In 1935 Bonhoeffer, who

strongly opposed the Nazis, decided to return to Germany where he became active

in several anti-Nazi groups. Bonhoeffer was apparently connected with the

assassination plot of 20th July 1944 when a group of military officers

attempted to overthrow the Nazi regime by killing Hitler. Bonhoeffer was

arrested and held in the Flossenburg concentration camp. On 9th April 1945, as

American forces approached Flossenberg, Bonhoeffer and six others, who had also

been involved in plots against Hitler, were executed.

The German Church

in Dacres Road was bombed and had to be demolished. The new church, opened in

1959, was named in memory of Dietrich Bonhoeffer. There is also a plaque on the

house in Manor Mount where he lived and a statue of him on the front of

Westminster Abbey, unveiled in 1998, celebrating him as a “protestant martyr”.

Both Janusz

Korczak and Dietrich Bonhoeffer are regarded as heroes and martyrs of the

holocaust who chose to die for their beliefs. That both should have such

significant links with Forest Hill is quite remarkable and something we should

celebrate.

Sources:

Annual Reports

and Management Committee minutes held at the Lewisham Local History &

Archives Centre

Information from

Marta Ciesielska and Bozena Wojnowska of the Warsaw Historical Museum, kindly

translated by Adam Kawecki

George Grove was born in Clapham in 1820, the son

of a fishmonger. He trained as an engineer, graduating from the Institute of

Civil Engineering in 1839. He travelled to Jamaica and Bermuda to oversee the building

of lighthouses. He also worked with Robert Stephenson on the Chester to

Holyhead Railway, helping build Chester Station and the bridge over the Menai

Strait.

George Grove was born in Clapham in 1820, the son

of a fishmonger. He trained as an engineer, graduating from the Institute of

Civil Engineering in 1839. He travelled to Jamaica and Bermuda to oversee the building

of lighthouses. He also worked with Robert Stephenson on the Chester to

Holyhead Railway, helping build Chester Station and the bridge over the Menai

Strait.